On the rails with the new freedom riders

by Ben Ehrenreich

| Catching Out I WON'T TELL YOU EXACTLY WHERE WE ARE, LEST UNION PACIFIC get wise and throw up another security camera, a few more reels of razor wire or some of those infrared sensors I keep hearing about. Suffice it to say that we're east of the river, not too far from downtown, and that there are a lot of train tracks around -- which is the point, really, since we're here to catch a train, but not Amtrak or Metrolink or anything so banal. We want a northbound freight, with luck one that will take us all the way up to Dunsmuir, just 50 or 60 miles below the Oregon line, in time for the annual hobo gathering there. |

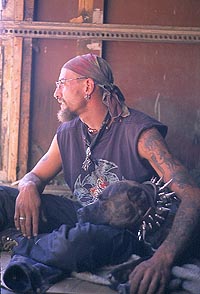

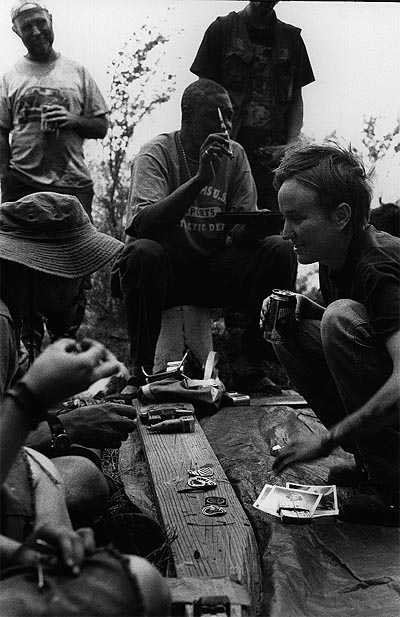

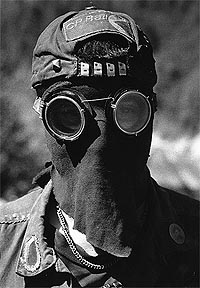

Crazy Angel and Meathead (Photos by Virginia Lee Hunter A.K.A. West Coast Virginia Slim) |

We heave our packs onto our shoulders and trek over mounds of concrete

and twisted rebar. We settle in a clearing surrounded by rusted truck

cadavers, their doors hanging open like broken wings, and listen to the

hissing of air brakes in the yard behind us, to the hum of the electric

wires, crickets chirping, and garbled orders from the Men's Central Jail

PA system echoing across the river. What we don't hear is trains. Forty

minutes go by, and not one has passed. "This is the waiting part," says

Clare. Virginia, who has four years of sporadic train-hopping under her

belt, nods in agreement. "This is what it's mainly like."

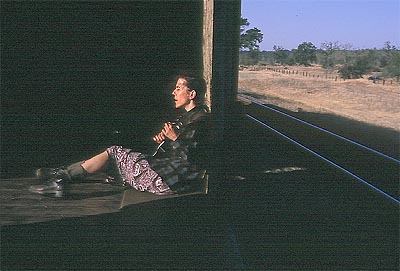

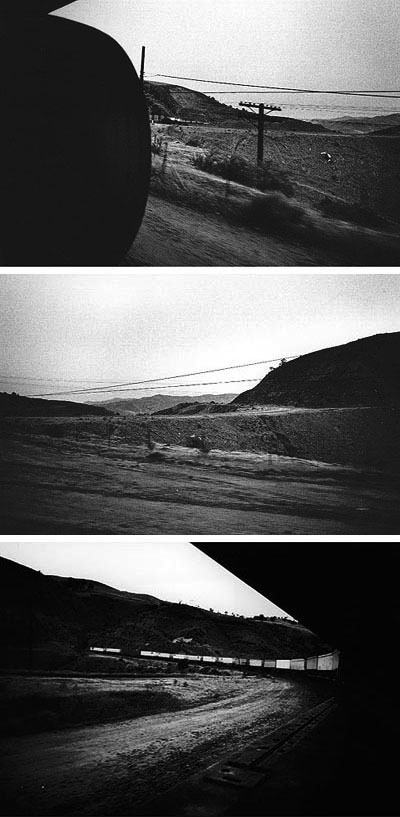

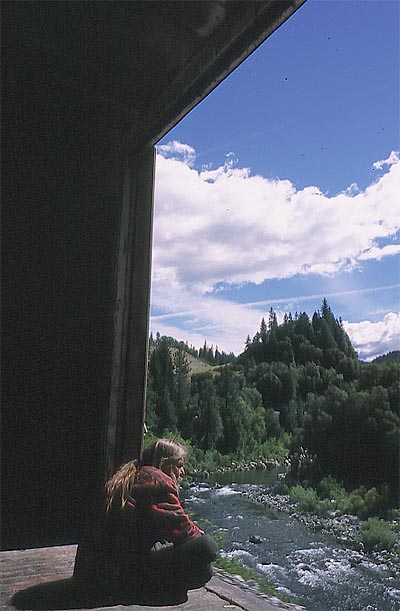

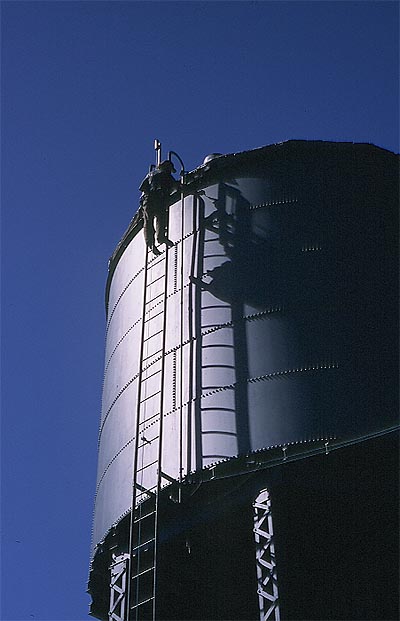

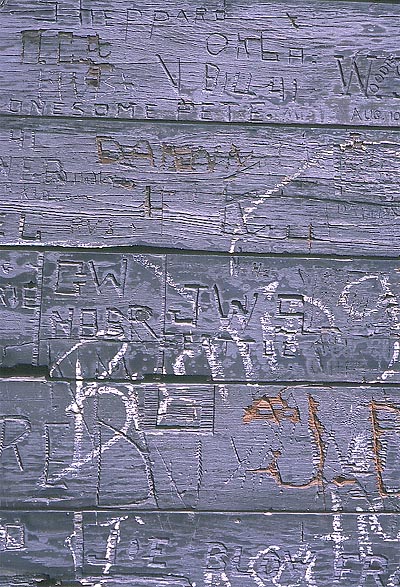

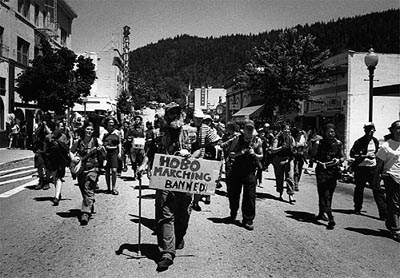

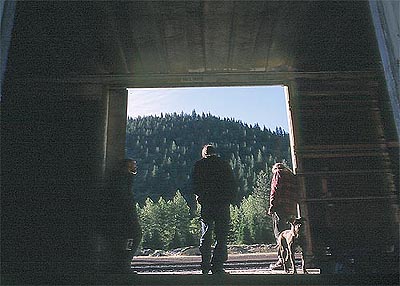

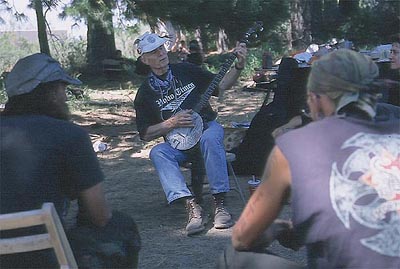

On the way to the Dunsmuir Hobo Gathering, Clare practices hobo songs on her ukulele. Virginia, Clare and I spend the night curled in our sleeping bags amid the chaparral and rubbish. Only two trains pass -- one heading south, and a northbound that could've been ours had a crew of workers not been laboring a few yards away. With dawn our camp is revealed in all its postnuclear glory. I find an empty backpack, a handmade shank with its blade snapped off, a spool of surgical tape and a Bible, one of its pages penciled full with Spanish scribblings. I can make out only one sentence: "Love is extinguishing itself." We return at night and are almost ready to give up when four locomotives roll slowly out of the yard, towing a northbound freight. They're gorgeous, sleek and huge and gleaming, all power and promise in the yellow lithium light. We jog through the gravel, lugging our packs and, running now, grab the ladder to a piggyback, leap up and pull ourselves on. A piggyback is a flat car that carries the ass end of a semi truck, just the cargo box and the rear axles. We jam our packs into the narrow spaces above the axles and hide behind the wheels. I curl myself as small as possible, dreading the beam of a spotlight, the bark of a cop. The train stops for five minutes and I do my best not to move. It picks up again, slowly, and the river snakes by to my right. The towers on Bunker Hill loom bright in the distance, looking sillier than they ever have before. We pass Main Street and are out of the yard, picking up speed. Sitting there, wedged in among brake hoses, fluid reservoirs and spiny metal things, with dozens of identical cars ahead of me and more than I can count behind, I panic for a second and ask myself, "Just where in fuck's name am I going?" Then a smile spreads itself across my face, and I don't care at all.  Tehachapi Pass at dawn. Goals WE'RE HEADING TO DUNSMUIR TO EXplore this curiously American phenomenon, which, despite rumors of its death dating back at least a half-century, seems to be catching on again. Men (and until recently, it has been largely men) began riding freight trains after the Civil War, when enough track had been laid to make it worthwhile, and enough dislocated veterans had become averse to staying still. Since then every major war and economic downturn has seen a return to the rails, providing a sort of shadow history of America, a constantly mobile underground of migrant workers, radicals, dreamers and thieves, misfits of all kinds who didn't mesh with the societal weave. During the depressions of the 1890s and 1930s, it was a common if not entirely acceptable way for working-class men to get around in search of wages. In the '30s, Frank Czerwanka, one of Studs Terkel's sources in Hard Times, recalled, "When a train would stop in a small town and the bums got off, the population tripled." The hobo's death knells began tolling shortly thereafter, and have been ringing ever since. Prosperity and the automobile kept people in houses and on the road, and by 1960, Jack Kerouac was blaming the hobo's death on the still-fledgling rise of the security state: "Today the hobo 's made to slink -- everybody's watching the cop heroes on TV." Though nearly every book written about hobos since then has mourned them as a dying breed, and despite all the cameras and infrared gadgets, thousands still manage to slip through Kerouac's "cop-avoiding night" to steal a little fast freedom from a shrink-wrapped world.  From the sublime . . . Today, except for immigrant workers eager to stay invisible, few ride the rails just to get from place to place. With all the risk and potential for mishaps, comic and tragic both, walking is almost more efficient. But since the early '90s, train-hopping has been gaining ground among a new generation of tramps. The grizzled old hobos may be dying off, but they're being replaced in boxcars and on the porches of grain cars by street kids, gutter punks, dreamy anarchists and eco-warriors, train-obsessed professionals, all held loosely together by a vision of freedom as old as the nation itself, an America of movement and self-reliance, of mythic vastness and silence, of discovery, escape, rebellion. It's an America that was offered long ago and never delivered, that we're all supposed to love but not allowed to look for, that's just around the corner and always out of reach.  . . . to the mundane - either way, no advertising The Ride THE WORLD LOOK S DIFFERENT FROM A freight train. There's no heat and no a/c. No meals are served. The restroom is wherever you find it. There are no buttons to push or cords to pull when you want off. The train goes where it wants when it wants to, and sometimes doesn't go at all. It doesn't care about your wishes. It doesn't like or want you, doesn't even know you're there. It can kill you without a thought, can leave you behind, maimed and bleeding, without a moment of remorse. There's no getting around it -- it's ridiculously romantic.  Ben, a crusty punk, tagging the Black Butte watering tank, built in 1926 We stay hidden as the train makes its way out of Los Angeles. Virginia's at the other end of the car, and I'm crouched beneath the axle beside Clare, a Web editor and sometime hobo who flew down from Berkeley to join us for the ride. We pass a Burbank strip mall, Krispy Kreme, Staples, Target, Best Buy, and I can't help but laugh out loud. All those packaged comforts, the shadowless, dust-free expanses of American convenience, exist now in another world completely. We thump off through the Vall ey, past auto-parts stores, taquer?s, the leering pink neon of motels and topless bars. The L.A. night slides by -- a different country, already far away. We leave the city and chug up through the mountains . It's too loud to talk. The train shakes out a cacophony that seems intentionally musical: a high-pitched squeal that varies from hiss to yawn with the steady bass rumble of the turning wheels, in turns cruel and joyful and terrifically sad, layered with the backbeat of the shaking steel car. I hold my ears as we echo through a tunnel and the high notes break toward painful.  Tags of yesteryear's hobos At around 3:30, the train shudders to a halt somewhere in the Antelope Valley. Bats flutter in the streetlights. After 10 minutes another train passes us, and we lurch on forward into the desert. We sleep for two or three hours, waking cramped under the axle, a cold wind blowing, our faces blackened with diesel smoke and dust. The sun rises and the air warms quickly. The Tehachapis roll by, golden on all sides, dotted with oaks and the occasional horse farm. We pack our gear and keep low behind the wheels until we've cleared the Bakersfield yards. After Bakersfield we fly, maybe 70 miles an hour, past rusting factories of corrugated metal, pink trailer homes, a man watering his lawn, sunflowers as big as your head. We speed through miles of vineyards and citrus groves, along Highway 99, past sprinklers irrigating green fields in great white arcs, past three men trying to free a forklift stuck in dried mud. It smells of fertilizer, cow shit, diesel. We do our best to sleep through the morning, chasing the sun across the floor for the heat. I wake and see a world that is green forever in every direction but up. Later, I open my eyes to a huge white silo, filling the sky like a spaceship. This is the West as hallucination, as fever dream -- as strange and beautiful as you always knew it was. Cows loiter in a flooded field. We pass a bowling alley, a truck stop, a burned-out nightclub, a street called Temperance Avenue, swallows diving over a field of corn, a Costco, a man standing alone beside the track, looking right at me but not seeing me at all.  New York Slim with Babys, a Chinese pug he rescued The Bull AFTER 13 HOURS, THE PIGGYBACK IS just starting to feel like home when we're spotted by Union Pacific police in a small train yard in the town of Lathrop, just outside of Stockton. The train has come to a stop, and as a whi te Ford Explorer pulls up in the gravel at the far end of the car, Clare begins to laugh. "Please step off the train," someone says, and Clare's shoulders start shaking. Funny time to laugh, I think. She covers her mouth to try and hold it in. " What?" I say. It seems Virginia had taken advantage of the train's stillness to heed nature's call, and was squatting over the edge of the car when the bull drove up. A stocky, pink man, he seems a little embarrassed -- pinker than usual perhaps -- but mainly pleased, like he's already looking forward to chuckling about it over a quiet beer after work. Clare doesn't have to wait, and is laughing openly when another Explorer stops beside us and we climb off too.  Tex leads the Hobo Marching Band in Dunsmuir's Railroad Days parade. The second bull, a compact Latino man in a blue uniform, asks Clare and me if we are associated with "the FRA." (He's talking about the FTRA, which stands for either Fuck the Reagan Administration or Freight Train Riders of America, and is alleged by everyone from Fox News to The Times of London to be a "gang of killers who prey on the weak" -- more on that later.) We are not. He asks me if I'm armed, asks where we're coming from, where we're going and if we've done this before, and seems as much motivated by curiosity as any putative intelligence-gathering. He takes our IDs, but doesn't bother to check them for warrants. He's almost apologetic when he finally hands us our tickets, citations for misdemeanor trespassing, and tries to make up for it by giving us directions to a homeless mission five miles off in Stockton, and offering a little advice: "Now you never heard this from me, but if you're going to ride freight trains, be careful, and I'd prefer you do it after dark." It won't be dark for seven hours, so we hitch a ride to a bus stop and two buses later are in Roseville. We hike from the station to the freight yards, and by midnight have found an open boxcar on a northbound train. (On the West Coast, northbounds generally carry empty lumber cars, which come back south piled high with fresh-sawed timber.) We climb in, spread our bedrolls in a corner and fall asleep to the sound of hammers clanking far off in the yard, and to the steady click and kiss of the idling engines, like someone spitting on a white-hot stone. Three hours later the car rolls out of the yard, and within a few minutes is speeding along, singing and pounding, its floor vibrating at a frequency that could iron out your elbows and turn your spine to jelly. For all that, a boxcar is a great ride. You have shelter from sun, wind, rain and the prying eyes of cops. If you're lucky and both doors are open, you have two huge bay windows and a choice of views. It's roomy, with a high vaulted ceiling, perhaps indifferently furnished -- some broken two-by-fours, stray cardboard -- b ut still bigger than a lot of apartments I've rented. Until last year, a boxcar could easily have fetched two grand or more a month on the Manhattan real estate market. I lie awake until the boxcar's groans and belches begin to sound like voices. "Shhh!" they say. "Last! Phhhh. Eat 'em! Pht! Eat 'em! Tsph. Get 'em out!" I drift off and wake in the mountains, in a forest of high firs. The earth is red here. We pass fingers of Lake Shasta, dotted with fishermen and kids on boats, the water clear and green. Purple wildflowers line the tracks; the Sacramento River flows fast and white beside us. Finally Mount Shasta appears, a giant ice-cream sundae of a hill, alone on the horizon, snow-topped and startling. We've arrived. The Convention DUNSMUIR IS A PRETTY LITTLE TOWN, nestled beside the river in evergreen hills, with a population (1,923) slightly lower than its altitude. It's been a railroad town for more than a century, a crew-change spot for the Union Pacifi c. It became briefly famous in 1991, when a train derailed and emptied a tank car filled with herbicide into the Sacramento, killing every bug, bird and fish for miles. It's been tidied up, I'm told. Today, railroad kitsch and fly-fishing are the staples of the local tourist industry, and this weekend, the trout are biting obediently and the Dunsmuir Railroad Days festival is under way.  Heading Home: Crazy Angel, Ben, Longhaired Donnie and Meathead On a wooded strip of land between the tracks and the river a 10-minute walk from town, the 2002 Dunsmuir Hobo Gathering has already begun. Only the old-timers have arrived, sitting in a clearing drinking beer until we trudge in and they all rise to greet us. North Bank Fred is here, an amiable local train-hopper and railroad nut who organized the Gathering, and who looks like a phys. ed. teacher gone slightly to seed -- always in red track shorts and sneakers, usually shirtless with a liter of Gallo white port in one fist. We meet a quiet silver-bearded man named Buzz Blur, who turns out to be a legendary boxcar graffiti artist, and the intensely friendly New York Ron, who speaks in a mile-a-minute upstate accent of a variety you don't hear much anymore. "I just got outta jail!" he says by way of gree ting, vigorously pumping my hand. "Congratulations," I say, unsure if that's the appropriate response. He tells me he got nabbed by the bull up in Klamath Falls, Oregon, after riding in all the way from Albany, and that he just finished an eight-year stint in a Montana prison (for what, exactly, I never learn). We meet a tall, slender m an with an easy smile who combs his long, yellow-gray ha ir with o bsessive regularity ("I'm a platinum blond," he laughs) and looks a bit like Donald Sutherland left out in the sun. He sticks out his hand and says his name with a grin: "No-Nuts." Later, we'll argue about who gets to ask him how he came to be called that, but it turns out it's no secret: He earned his name the hard way in Vietnam. We meet a bearish fellow named Tennessee, and the voluble Silver Miner Larry, a fast-talking tramp with short gray hair, his eyes a little loose in their sockets. He introduces his old lady, whose name is either Kimberly or Bert or Whistle Britches, depending on whom you ask, and who, before the weekend is over, will somehow manage to break her leg in three places while squatting to pee.  The trading blanket: Hoppers negotiate for train patches, old railroad dated nails, hand warmers, etc. That night we bring a pint of whiskey over to the clearing, expecting to find a crew of beer-happy tramps to share it with. Instead there's just Tennessee, sitting alone in the dark, working on one last 12-pack of Natural Ice. Over the next few days I will never see Tennessee sober, neither at 9 a.m. nor midnight. Nor will I ever witness him being anything but gentlemanly, regardless of his c ondition -- he will one afternoon rouse himself unsolicited from what looks like a near-comatose state to help me lug a couple bulky 25-pound packs a quarter-mile down the tracks. He's bearded and a little shaggy, like Santa's wayward younger brother, with fists large enough to make the beer cans they continually clutch look like they belong in a dollhouse, and a North Florida drawl as thick as his forearms. He complains of a Siskiyou County sheriff's deputy named Stuart, who lives around the bend and will prove to be no end of trouble. "Excuse my language," Tennessee says, "but he's a real fuckin' prick." Just the other day, he says, he was walking over the bridge to the Texaco on a beer run, when Stuart stopped him. He ran his ID for warrants and found none. ("I'm unwanted," Tennessee says.) "He said, 'Why don't you get out of here?' I said, 'Where you want me to go?' He said, 'Just go. I don't care where. Go to Roseville, Klamath Falls , Eugene, Reno, Elko, I don't care, just get outta here.' I said, 'I been to those places, and they all told me the same thing. Except they said come here.'" Tennessee sips the whiskey gratefully, chases it with beer, then holds forth on the nemesis of West Coast tramps, the bull in Klamath Falls, a certain Roger the Dodger. Roger the Dodger < br> EVERY WORLD AND EVERY ERA NEEDS its myths, its saints and its demons, and this one is no exception. Meet Roger the Dodger, a trickster-devil for the epoch of the corporatized rails. Not that he's not real -- even those who doubt his omnipresence and scoff at his legendary powers affirm that Roger does exist. Like Lucifer, he stood among the angels once. Back before Union Pacific bought out Southern Pacific, Roger was a friend to the tramp. He was hard but kind, and made only two demands: "Stay off of my money, stay off of my power." So long as he didn't catch you riding a hotshot (a high-priority train towing particularly valuable freight) or stowing away in one of the rear locomotives, you could count on a smooth ride through K-Falls. If you abided by his rules, he'd let you be, and might even tell you when your train was leaving, and on which track. But after the buyout, legend has it, the corpora te powers put the screws on -- if Roger wanted his job and his pension, he'd have to bust some tramps. He took to his task with all the zeal of the converted. If you can believe the stories, Roger the Dodger never sleeps. He works no fixed hours and knows the tracks like the veins in his arms. You've got a slim chance passing through K-Falls under cover of night, but in daylight it's near impossible, says Tennessee: "He'll get you, Roger will." It was Roger who got New York Ron, fresh from the Montana pen, and kept him in the tank for two days with the snoring drunks and, Ron says scornfully, "no shitter, just a piss hole." Roger keeps a book two inches thick containing the name of every tramp he's ever come across, says Ron. Their only other encounter was 10 years ago, but Roger remembered the name and flipped straight to the tattered page. So if you choose to ride the rails, take Tennessee's advice, and "Watch out for old Roger" -- no matter where you are. "I've even seen him right here," Tennessee swears, "under that bridge." Tennessee is not joking, but Roger's not there now, and won't be tomorrow either, though a steady stream of tramps will be coming up the tracks all day long. Save for a few stragglers, everyone will be here by afternoon, and before they all arrive, some introductions are in order. The Tramps TODAY'S OLD-TIMERS, OF COURSE, ARE not the old-timers of yesteryear. Even a decade ago, there were still a few left who'd been tramping since the hobo glory days of the Depression. Most of them are now dead or indoors, and a generational shift has occurred. The romantic hobo of kitsch and legend can be safely buried. The old-timers of today hit the rails in the '60s and ear ly '70s, most after coming back from Vietnam to a country into which they no longer quite fit. Others were casualties of the '60s drug culture who either lost everything or decided after some consideration that Main Street America was worth avoiding. As harmless as most of them now seem -- usually blind drunk, and pretty damned rickety even when they're not -- they're a gristly bunch. More than a couple of those present are members of the aforementioned organization, the FTRA, the object of a storm of media hype in the 1990s, when they were blamed for a string of murders. Most of these turned out to be committed by one man, Robert "Sidetrack" Silveria, who confessed in 1996 to killing 28 tramps. It's not even clear that Silveria ever claimed to be in the FTRA, but the reputation stuck, and whenever a newspaper or tabloid-news show wants to warn kids to stay in their cars and in their bedrooms, they trot out "the killers of the rails."  SocX and Ultra Heather trade while New York Slim offers up a Leatherman tool. You've met a few of the old tramps already. There's also New York Slim, a 6-and-a-half-foot black man with an enormous laugh and a tiny, cockeyed dog. Only the white hairs in his beard give away his age -- without them he could pass for 40. He survived a POW cam p, but stays sober and radiates calm. Slim's generosity and easy regality win him the instant loyalty of almost all the younger tramps. He complicates the common assertion that the FTRA is a white-supremacist group: A couple of members do have swastikas tattooed on their arms, but Slim is not only accepted, he's treated with more respect and deference than anyone else around. These days he's rubber-tramping, getting around in an old blue pickup rather than by rail. Then there's Magoo, who, like Tennessee, is never without a beer in one hand, sometimes with a pint of whiskey in the other -- even shortly after sunrise, still sitting on his bedroll. "They call me Magoo," he tells me, "because I can't see past . . ." he pauses for a good 10 seconds before coming up with ". . . dusk." It's often hard to figure out what Magoo is saying, n ot only because of the drunken circuitousness of his conversation, but because he laughs his way through most everything he says. There's also Longhaired Donnie, not a vet ("I got a wing-nut pass," he explains, "but I can't get a wing-nut check. Figure that out.") and not an FTRA member, "just an old hippie." With his long brown beard and crumpled face, he looks like a wrinkled elf, though his eyes don't start twinkling until he's had a few beers. Finally, Crazy Angel is only 29, and thus hardly an old-timer. But he's been riding the rails since he was 14 ("I don't kno w," he shrugs wh en I ask him why he started, "I got tired of all the bullshit"), and mainly hangs with the older tramps. When I first see him it's like a vision out of The Road Warrior -- he's tall, lanky and long-limbed, and walks down the tracks a stride behind his pit bull, Meathead. The dog wears a collar studded with 2-inch steel spikes, carries his own food and water in woven-leather saddle bags, and is so well-trained he might as well speak English. Crazy Angel's muscled arms are tattooed with grinning skulls, the letters FTRA, and a big red swastika. His nose and lip are pierced with hoops, a metal spike protrudes from his brow, and he has puzzle pieces tattooed on his shaved skull. Behind his glasses, though, Crazy Angel's eyes are s hy and questioning. He speaks in soft, gentle tones, and laughs a goofy stoner's giggle. When asked how he got his name, he blushes a little and says sincerely, "I guess it's 'cause I'm a nice guy." And he is. Crusties IF THE OLD-TIME TRAMPS ARE THE PAST, fading as fast as their overworked livers, train-hopping's future likely lies with crusty punks -- street kids so named for both a frequent disregard for hygiene and a bristly punk-rock attitude. There are plenty of ot hers taking to the rails these days, but most of them do it part-time. The crusties, who at this particular gathering are rather slimly represented, are more often homeless, and if they can get as romantic about trains as anyone else, they also ride them out of sheer practicality. |

| Take Rocco and Ben, who've been traveling together for more than two years. Rocco, 23 and the more voluble of the two, hails originally from Virginia and most recently from San Diego. He's got short black hair, hated is tattooed on his neck (it was hate originally, before he added the d), and he dresses in standard crusty fashion: faded black Slayer T-shirt, cut-off Carharts patched and repatched, so well-worn they look like leather. "Wh y I started," he says, "is because I got kicked out of my house." He was 17, using a lot of crystal, living on Ocean Beach and looking to get straight. "I never thought about being on the streets," he says. "I was like, 'What the fuck? How do you sustain? How do you eat? What do you do?'" He met a kid who told him he'd just come in on a freight train. "It was like Ding! -- the light bulb -- 'Why did I not think of this?'" |

Rocco in his winter riding gear |

|

He left with no goal in mind except "to get the hell out of there." His

first ride took him to Mexico by mistake, the next one to Barstow, where

he stayed in a mission for a while. "I don't do homeless missions

anymore," he says. "I can depend on myself more." He Dumpster-dives for

food, panhandles, works when he can. "If you're starving in America,

you're a fool."

Despite the anarchist tattoo on Rocco's arm, he doesn't see train-hopping in any explicitly political context, except as rejection and flight. "The way we live is not acceptable to society." The distaste is mutual: "I don't care for greed," he says. "That's why society's so filthy and shitlike." Roc co tries to downplay his love of trains -- he rides because, he says, "I don't want to be bound by anything. I don't want to be tied down." But he has a boyish enthusiasm for big machines, and a hard time keeping it from showing. "For me it's to escape. And it is my transportation, like people use their cars. I really love it," he concludes, waving his hands in frustration, unable to express the depth of his feeling. His partner, Ben, taller and more reserved, will later open up over a few beers and put it like this: "Sometimes I feel like I'm the richest guy in the world. I could've set out to make a million dollars and never seen the things I've seen. But I didn't. I decided to be poor." Pixies THEY ARRIVE IN GROUPS OF 10 OR 12 at a time, around 40 of them altogether. Most are in their early 20s and look a lot more prosperous and middle-class than the crusties: Their faces are rounder; they wear Tevas rather than combat boots and carry expensive camping gear instead of battered army-surplus packs. Despite the road dirt and the long trip, they glow with youthful exuberance and hardly rest before they begin sorting lentils and chopping potatoes for a big vegan mulligan stew. Enough came from Santa Cruz that they had to meet before they left and divide into three shifts to preven t dozens from descending on the train yards all at once. Many of them haven't hopped before, or have done so only rarely, and most, when asked what got them interested in hopping, say the same thing: "Lee."  Banjo Fred performs at Black Butte camp. Lee Desaux, 47, is a sort of Pied Piper of Santa Cruz, where he's been living in well-appointed squats in the woods for more than a decade. Invariably dressed in torn cutoff black sweatpants and boots, his neck and arms bejeweled with aluminum hose clamps, Lee's been riding since 1986, and introducing the barefoot and besandaled, eco-radical, neo-hippie set to the rails for almost as long. For Lee, and most of the Santa Cruz crew, train-hopping is a beautiful way to see the country, a source of community and, he says, with trademark squinty smile, "a natural extension of our visions and lifestyles." It's a way to get around without buying into the money economy, a way of consuming without waste, of living off the leftovers of American abundance in the same spirit as squatting unused land and subsisting on food that grocery stores and restaurants discard. Freight trains are like a communal garden that moves. Espresso LAST COME THE YUPPIE HOBOS, IN wh ich category I include not just the ones whose cell phones wake them up on boxcars, but all those folks with homes and jobs somewhere who could afford Amtrak but ride the rails because they love it. Some make occasional long-weekend excursions, others organize their lives around trains. Take Clare, who rode with Virginia and me up from L.A., but fell ill shortly after arriving in Dunsmuir and left for home. She does freelance work in what's left of the Bay Area's e-economy and has taken a handful of freight journeys over the last few years, once as far as Iowa. She likes the adventure, she tells me on the phone a couple of weeks later, and the fact that "When you're traveling by freight train there's no advertising pointing at you. You go through the back yard of America" without a billboard in sight.  Longhaired Donnie and his new girlfriends from Santa Cruz Or take a hobo couple, one member of which will later e-mail me to ask that their names not be printed here. He lives in the Midwest and reviews grant proposals for a living; she's an ornithologist based in California. They met in a rail yard three years ago. Both work freelance, and work just enough to be able to devote about half of their time to train-hopping, riding back and forth across th e West to see each other. Or take SocX, pronounced socks -- it's a complicated pun decipherable only by train freaks, but yes, it does refer to his hosiery, which is enviably colorful. The 25-year-old sound engineer with an apartment and a girlfriend back in Nashville took two weeks to get here. He started riding short hops with a friend when he was 17 and was thrilled to learn later that "This isn't just a mode of transportation, there's a culture here." He rides as often as he can and absorbs the minutiae of railroad history and lore like a sponge soaking up diesel. "I'm one of the complete nutcases," he says. "If you would take a microscope to me, you'd see there' s trains running in my veins." Train-hopping is uncomfortable and dangerous enough that it's rare ly just a recreational activity: Most of the yuppie hobos are seriously obsessed. They can talk trains for hours, which is good, because the tramps and the more experienced crusties and hippies can as well, so everyone gets along, more or less. And the yuppie hobos often carry espresso pots, which everyone appreciates. The Law OUR FIRST MORNING IN DUNSMUIR, the espresso pots have not yet emerged from the rucksacks, so we head into town for eggs and bacon. On our way back, a mope y young man who calls himself Papa Dalek tells us that Siskiyou County sheriff's deputies have shown up at the campsite and, with shaky legal reasoning, ordered everyone to clear out. People were trespassing on private land, they were drinking in public, it didn't matter what they were doing, they had to leave. At a bend in the tracks, we meet Rocco and Ben, who are waiting there to give new arrivals the options. The old-timers are heading off to a place called Black Butte, they tell us, about a 15-minute drive away. The rest are camping at another site downriver, a little farther from town and, we hope, from the consciousness of the sheriffs. We head for the latter, a high, sloping fie ld on the other side of the tracks, thick with poison oak. It's not long before Ben and Rocco turn up -- they were just chased off by four sheriffs toting shotguns and a dog. Eight kids from Santa Cruz, their faces still blackened with freight-train grit, arrive looking shaken -- they too were greeted by the sheriff's impromptu welcoming committee. Later, another group of Santa Cruzians who left their packs at the original camp and hiked off to the waterfall upstream to frolic and bathe will return and find the site abandoned, their packs emptied and the contents strewn about the woods. They will find their sle eping bags hanging from trees, bags of food and spices emptied in the dirt, $20 of food stamps torn apart. A tall, skinny 21-year-old with short blond hair who goes by Buffalo Alice will find "all my personal possessions -- passport, pictures, letters, everything -- scattered and in the bushes." An earnest, bearded substitute teacher named Doug (hobo name: D-Rail) will search for one of his boots but never find it. Though no one will have seen the culprits, no one will doubt their identities. Campfire Symphonics NOR DOES ANYONE WANT TO LET THE police spoil a good time, so once the sun goes down and the lentils are gone, the beer starts flowing. A few Santa Cruz kids break out guitar s and begin singing songs about friendship, multinational corporations and pollution. Rocco tells me about his father, who was once in the military, assigned to some highly secret unit trained to kill people quietly in foreign lands. Now he's a cop, and sounds like a real piece of work. Rocco's clearly pretty broken up over the guy. He's also concerned about my motivations, concerned I'll write something sensationalistic and exploitative. He says he doesn't think society deserves to know about this world, that people haven't earned it. Maybe he's an elitist asshole to think that, he says , but that's how he feels. Some kids from Portland start playing old bluegrassy hobo favorites on fiddle and guitar, and as I retreat to my sleeping bag I hear the whoops and stomping feet of the dancing pixies drifting up through the trees. Lying there in the dark, I consider what Rocco has said, what everyone else has told me, and I understand that this is about community, about finding a group of like-minded folks outside the usual channels, but also about creating a realm of skill, of secret knowledge, virtue and style, that the scared and intolerant residents of comfortable straight society cannot touch or understand. And Rocco does not want them to understand. They have their own culture, and it's because that culture is so insipid and co rrupt that he sleeps out of doors. Hobohemia, to borrow a term coined by the anarchist Ben Reitman in the '30s, is a separate world, and defiantly so. It has its own rules and rewards, even if the rules are rarely followed and the rewards frequently fail to materialize. It's a secondary track off the American mainline in which courage and independence still matter, in which freedom is not abstract but palpable, and easily distinguishable from its opposites -- work, stasis, jail. This is true for the idealistic Santa Cruz kids as much as it is for home less punks like Rocco, though for many of the former the risks are smaller. And it's certainly true for the old tramps. All share a disappointment, to varying degrees and in divergent ways, a nostalgia for an America that's failed to become, the one we were promised in grade school, allegedly passed down to us by vision-rattled heretics and daring claustrophobes, an America already lost by the time Whitman and Thoreau claimed to have found it, still a sustaining memory for the Beats and the hippies and even the fuck-off-and-leave-me-alone punk rockers. Turning on my side, I can see Rocco standing by the fire looking glum while the Santa Cruz kids go on singing about being free, treading softly on the earth and loving one another. Then a train goes by on the tracks below and silences them with its wails, and the train's song seems to have lyrics this time, to sing of all that yearning, all the failed dreams left to hang immaterial on the edges of cities, beneath cement overpasses, in riverside jungles and hard urban squats, all that space and longing squeezed into this rhythmic yowl and clang. Everyone falls silent. The guitar and the fiddles stop, and maybe I'm drunk and sentimental and imagining things, maybe it's just late and everyone is tired, but it seems the train sang for them better than they knew how, and when it passed there was nothing left to do but stumble off into the woods and search out a piece of ground flat enough to sleep on. Railroad Daze IT'S A HOT AND CLOUDLESS DAY. TOURists and locals line the street in lawn chairs to wait for the Railroad Days parade. First come the VFW, old men marching stiffly in uniform, guns and flags on their shoulders. They're followed by a little girl dressed as the Statue of Liberty; some Boy Scouts; two kids cruelly encumbered with sandwich boards advertising Better Home Realty; seven vintage Corvettes; a few shiny fire trucks; a grinning boy in a go-cart labeled the "Osama yo mama Payback mobile"; a truck painted camouflage topped with waving children and a banner advertising Bullseye Tactical Firearms Training ("Protect Your Family and Yourself"). An old Ford tows a covered wagon, manned by a family in pioneer drag. The wagon is sponsored by the Dunsmuir Church of Christ, emblazoned with flags and painted "All Aboard America, One Nation Under God." Finally, amid this panoply of patriotism, claiming another branch of Americana, the Hobo Marching Band arrives -- though this year their sign, in honor of the sheriff's shenanigans, reads "Hobo Marching Banned." An old tramp named Tex, who lives in a munit ions dump outside of town, heads the group, hobbling along with a cane. Beside him is Banjo Fred, a ghostly codger who leads the ragtag, sunburned group in a rousing version of "This Land Is Your Land." Barefoot, dreadlocked kids skip and dance and beat away at frying pans, empty water bottles and upturned buckets. The onlookers seem torn: Some laugh and cheer, others watch silently, sullen and suspicious. "Well," says Banjo Fred when it's all over, addressing no one in particular, "if we didn't make an impression, I don't know what would." There's a stage set up on a side street, nestled among crowded booths selling tri-tip sandwiches and "Protected by Smith & Wesson" T-shirts. The kids from Portland who played at the camp last night take their seats. They're the Old Timey String Band, and they play their old-timey m usic to appreciative hobos, who dance and stomp and whoop it up in the hot sun without any sign of tiring. No locals join in. Rocco an d Ben look on in baffled silen ce. Half an hour goes by, and Rocco shakes his head: "Man, these kids must eat better than I do." Another hour passes. It only gets hotter, but the kids are still clapping and twirling, dousing themselves with water to keep cool. "We need to have a country all our own," Rocco decides. "It would be like this, all the time." Black Butte THE BAND'S SET ENDS AT LAST. A COUPLE of hours later, to avoid further run-ins with the sheriff, everyone packs up and moves out to Black Butte, an idyllic meadow of wildflowers and fragrant grasses a few miles up the tracks, between Mount Shasta and the tower of rock that gives it its name. For two days, train talk echoes around that meadow, pausing only when a train goes by. Debates rage over which is the longest tunnel in the country, which the highest pass. Most of the stories are tales of hardship, told now with a laugh, of frigid nights going through the Donner Pass by mistake without even cardboard to keep you warm, or of trains that stop and sit for days in the Mojave in midsummer. Ben tells of being so cold one Wyoming winter he had to stand all night because the soles of his shoes were the only part of him that wouldn't freeze instantly to the boxcar's steel floor. New York Slim tells about the guy whose face froze to just such a boxcar floor, and how they had to heat the metal with torches from beneath to melt him free. The stories dissolve into a sea of place names -- Marysville, Eugene, Pocatello, Livingston, Ogden, Evanston, Sparks, Colton, Whitefish, Green River, La Crosse -- an atlas of laughter and survival. Crazy Angel keeps an e ye on Meathead to make sure he doesn't get too close to New York Slim's dog Babys, a snaggle-toothed little puff of white and brown fur that Meathead would barely have to open his jaws to swallow. Meathead's fine with people, Crazy Angel tells me, but he's "kind of antisocial" when it comes to animals. In other words, "he likes to kill them." Meathead would prefer a world stripped of all non-human fauna, and does what he can to push things in that direction. So whenever he gets within 10 yards of Slim's pet, Crazy Angel issues a string of commands, each one more or less instantly obeyed: "Meathead, go over there. By the gear. Not there. Over on the other side. A little farther. To the right a little. Farther. Now lie down. Good dog." Sitting on his bedroll, old Magoo calls Meathead over. He hugs him and kisses his brindled nose. No-Nuts laughs and suggests that the two look alike. "Only difference is Meathead combs his hair better," he says. Later, Magoo sits perched on an overturned bucket with a couple of drunken crusty punks and a pensive-looking Ben. He talks about Vietnam. He was there early on, from '61 to '63, sent not to fight but to "teach." He gestures with his beer can, marveling at the word. "They killed a lot of my friends," Magoo says. "And I got good at killing them. And I got to like it." His eyes are wide with residual wonder, still shocked by this strange fact: "I got to like it a lot." Ben is silent. The drunk punks talk about hitching into town to do some panhandling. "I was there two years without even getting athlete's foot," Magoo goes on. "I wanted to get shot, I just wanted to get out of there, but I couldn't." Magoo starts in on a story about a reconnaissance mission. It's a bit hard to follow. "They told me to find 'em. 'Find 'em or kill 'em?' I said. 'Find 'em,' they said. 'Okay,' I said. And I found 'em." Ben gazes sadly at the ground; the punks aren't listening at all. Magoo is "four clicks up the crik" when he loses track of the story entirely and gives up. Catching Out (2) AFTER TWO DAYS OF LAZING ABOUT AT Black Butte, eating pancakes cooked over a barrel fire on a greased-up sheet of scrap metal , drinking around that same fire beneath a sky perilously heavy with stars, we say our goodbyes. New York Slim gives us a lift back to Dunsmuir in the back of his truck, a tarp pulled over our heads so the police won't have cause to stop him. Seven of us are heading south: Virginia, myself and a schoolteacher from Topanga named Jacob; Steve and Jodie, recently arrived from Portland; Longhaired Donnie and Crazy Angel. Meathead the Dog makes eight. We miss one train just as we get into the yard, and run up to the Texaco to buy food and water for ourselves and beer for Donnie. This will be, he tells us, his last ride. He's got an appointment in Roseville for an operation on his eye ("a floater"). His liver is bad, and he has a hard time keeping up. "I'm just an old sore, I guess you could call me, one that never healed," Donnie smiles sadly. He started riding in the early '60s, and has done so ever since, sometimes staying put for a while, working, even owning a business, losing everything to drugs and prison. Riding the rails is the only thing he ever found that could keep him off heroin, he says, and thereby out of trouble. "I called my grandma before she died. I said I finally found my niche." Walking along the tracks through the town with Crazy Angel, I note how quiet it is. "It's nice," he says. "There's no people around. I hope they stay in their houses." He tells me he travels to keep sane, that he doesn't like being around people too often and never learned the skills necessary to rent an apartment, pay the bills and get by in one place. He refers to the house-bound populace as "citizens," and regards them not with hatred ("Hate's a bad thing") but with the mistrust one reserves for unfamiliar be asts, as if they belong to a different species entirely, one possessed of wood and drywall exoskeletons, which they shed occasionally to crawl out and make trouble for tramps. With a sheepish smile he tells me his name for the scent a tramp develops after a few weeks on the road without bathing: "citizen repellent." Donnie and Crazy Angel reminisce about the old days, before intense corporate security made tramping so difficult, when you could ride from New York to California without a hassle, when you could hop into any town in the country and find 15 of your friends. Even a decade ago, Angel says, you could camp in the yards without trouble from the bull. You could leave all your gear in the jungle without fearing it would be stolen, says Donnie, and you didn't have to worry about young punks wanting to fight you to give themselves a name. They talk about old friends who've died, others locked away for good. Donnie shakes his head. "It ain' t nothin' like it used to be. Nothin' at all." No trains come through that night, and we sleep in a clearing beneath the tracks. Meathead has his own sleep sack, and a hooded sweat shirt for the cold. I wake at dawn to the sound of a whistle blowing. Crazy Angel is up and out of his bag, and by the time he says, "Wake up, Donnie -- southbound's coming!" e veryone else is awake too. We pack hastily, and climb the embankment to the tracks. Angel spots an open boxcar, and we all hoist ourselves up and in. "Jump, dog," orders Angel, and Meathead jumps in too. The train sits. After an hour the sun rises over the hills, the light angling softly into the car. Donnie rolls a cigarette, and the smoke rises in the sunlight in little curling dragons. Another hour passes. Jodie reads a book. Steve stands on the track and juggles stones. Angel sews a leather pouch. Donnie tags the wall of the car with a Sharpie. He writes his name, and then "To Love/Is to Sacrifice/To be Loved/Is to Cherish!" After another hour a southbound hotshot speeds past. The air brakes on our train hiss, then click and squeak. The boxcar shivers. Its walls moan, and the green world glides slowly by outside the door. Note to the curious: Like driving automobiles, falling in love, and speaking your mind in public, train-hopping is dangerous. Reall y. To view more of West Coast Virginia Slim's train-hopping images, visit her site... |